Call it the paradox of the modern dictionary. We’re in a golden age for the study and appreciation of words—a time of “meta awareness” of language, as one lexicographer put it to me.

Dictionaries are more accessible than ever, available on your laptop or phone. More people use them than ever, and dictionary publishers now possess the digital wherewithal to closely track that use.

Podcasts, newsletters, and Words of the Year have popularized neologisms, etymologies, and usage trends. Meanwhile, analytical software has revolutionized linguistic inquiry, enabling greater understanding of the ways language works—when, how, and why words break out; the specific contexts for expressions and idioms. And all of that was true long before the rise of AI.

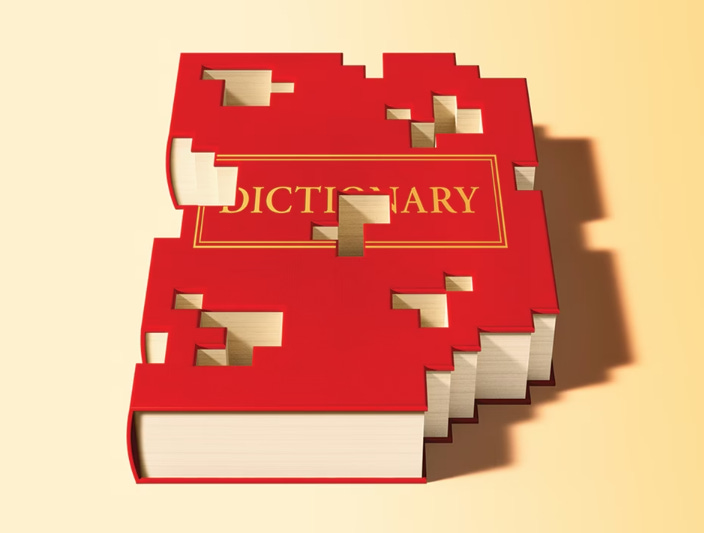

But these advances are also strangling the business of the dictionary. Definitions, professional and amateur, are a click away, and most people don’t care or can’t tell whether what pops up in a search is expert research, crowdsourced jottings, scraped data, or zombie websites.

Before he left Merriam, John Morse told me that legacy dictionaries face the same growing popular distrust of traditional authorities that media and government have encountered.

Read more | THE ATLANTIC